750.3 Bridges

| Asset Management |

| Report 2009 |

| See also: Innovation Library |

750.3.1 Hydraulic Considerations for Bridge Layout

750.3.1.1 Abutment Layout

Abutments shall be placed such that spill fill slopes do not infringe upon the channel; the toes of the spill fill slopes may be no closer to the center of the channel than the toe of the channel banks. The Soil Survey provided by the the Geotechnical Section gives minimum spill fill slopes based on slope stability criteria. The minimum bridge length for stability criteria is thus determined by projecting the stability slopes outward from the toes of the channel slopes as shown below. For structures crossing an NFIP regulatory floodway, abutments shall be placed such that the toes of the spill fill slopes are outside the floodway limits.

750.3.1.2 Pier/Bent Layout

Piers should not be placed in the channel except where absolutely necessary. Where possible, piers are to be placed no closer to the center of channel than the toe of the channel banks. When the proposed bridge length is such that piers in the channel are necessary, the number of piers in the channel shall be kept to a minimum (See Abutment and Pier Location Limits above).

Bents shall be skewed where necessary to align piers to the flow direction, at the roadway overtopping design criteria, to minimize the disruption of flow and to minimize scour at piers. For stream crossings, skew angles less than 10 degrees are not typically used, and skew angles should be evenly divisible by 5 degrees.

750.3.1.3 Roadway Fill Removal

When replacing an existing bridge, the bridge memorandum and design layout should note whether the existing roadway fill is to be removed. The designer should consult the district in regard to the limits of fill removal. Minimum removal should provide hydraulic conditions that minimize the bridge length. Normally, existing fill is removed to the natural ground line. The removal limits of existing roadway fill will be shown on the roadway plans.

750.3.1.4 Velocity

Average velocity through the structure and average velocity in the channel shall be evaluated to ensure they will not result in damage to the highway facility or an increase in damage to adjacent properties. Average velocity through the structure is determined by dividing the total discharge by the total area below design high water. Average velocity in the channel is determined by dividing the discharge in the channel by the area in the channel below design high water.

Acceptable velocities will depend on several factors, including the "natural" or "existing" velocity in the stream, existing site conditions, soil types, and past flooding history. Engineering judgment must be exercised to determine acceptable velocities through the structure.

Past practice has shown that bridges meeting backwater criteria will generally result in an average velocity through the structure of somewhere near 6 ft/s. An average velocity significantly different from 6 ft/s may indicate a need to further refine the hydraulic design of the structure.

750.3.1.5 Hydraulic Performance Curve

The hydraulic performance of the proposed structure shall be evaluated at various discharges, including the 10-, 50-, 100-, and 500-year discharges, which are the discharges typically found in a Flood Insurance Study. The risk of significant damage to adjacent properties by the resulting velocity and backwater for each of these discharges shall be evaluated.

750.3.1.6 Flow Distribution

Flow distribution refers to the relative proportions of flow on each overbank and in the channel. The existing flow distribution should be maintained whenever possible. Maintaining the existing flow distribution will eliminate problems associated with transferring flow from one side of the stream to the other, such as significant increases in velocity on one overbank. One-dimensional water surface profile models are not intended to be used in situations where the flow distribution is significantly altered through a structure. Maintaining the existing flow distribution generally results in the most hydraulically efficient structure.

750.3.1.7 Bank/Channel Stability

Bank and channel stability must be considered during the design process. HEC-20 provides additional information on factors affecting streambank and channel stability, and provides procedures for analysis of streambank and channel stability. At a minimum, a qualitative analysis (HEC-20 Level 1) of stream stability shall be performed. If this qualitative analysis indicates a high potential for instability at the site, a more detailed analysis may be warranted. See the AASHTO Highway Drainage Guidelines Chapter VI and HEC-20 for additional information.

750.3.1.8 Scour

| Asset Management |

| Report 2009 |

| See also: Innovation Library |

Hydraulic analysis of a bridge design requires evaluation of the proposed bridge's vulnerability to potential scour. Unanticipated scour at bridge piers or abutments can result in rapid bridge collapse and extreme hazard and economic hardship.

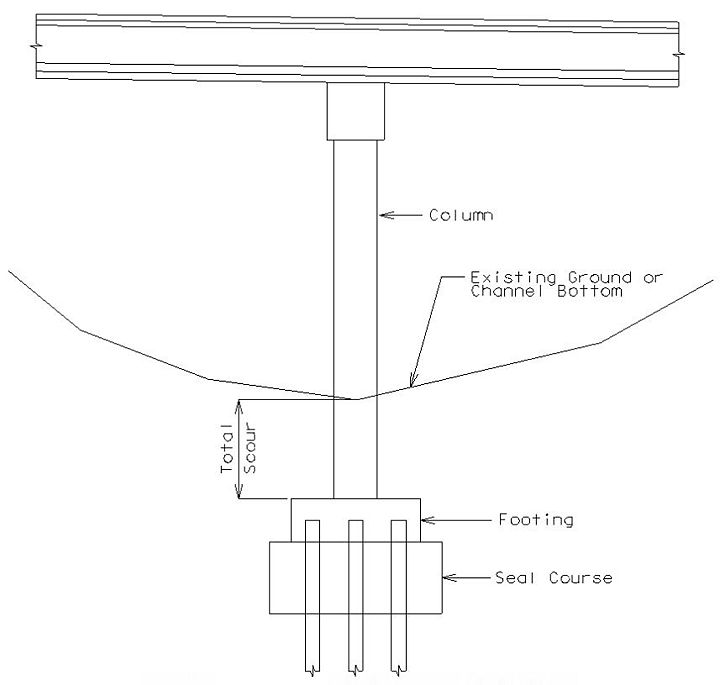

Bridge scour is composed of several separate yet interrelated components, including long term profile changes, contraction scour and local scour. Total scour depths are obtained by adding all of these components together. All bridges shall be evaluated for the scour design flood and scour check flood frequencies shown in the table below.

| Roadway Overtopping Design Frequency | *Scour Design Flood Frequency | *Scour Check Flood Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Q25 | Q100 | Q500 |

| Q50 | Q100 | Q500 |

| Q100 | Q200 | Q500 |

| * The Overtopping Discharge and Frequency shall be evaluated as a flood scour event if it has a lesser recurrence interval than the scour design flood or scour check flood (AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications 2.6.4.4.2, and HEC-18). | ||

Lateral channel movement must also be considered in design of bridge foundations. Stream channels typically are not fixed in location and tend to move laterally.

For additional information on scour and stream stability, see HEC-18 and HEC-20.

750.3.1.8.1 Pile Footings

The top of pile footing elevations should be set at or below the calculated total scour design depth, provided the calculated depths appear reasonable. Consult the Structural Project Manager in regard to footing elevations if Total Scour design depth is less than 6.0 feet. Top of footing elevations on the overbanks should be designed at the same elevation as footings in the channel unless it can be determined with a reasonable degree of certainty that the channel will not migrate into the overbank during the life of the bridge. The bottom of footing elevation shall remain the same whether a seal course is used or not; do not adjust the bottom of footing if a seal course is used. Considerable exercise of engineering judgment may be required in setting these footing depths.

750.3.1.8.2 Spread Footings

Spread footings shall be keyed into the rock to prevent sliding and to protect the footing from scour. Keys shall be a minimum of 6 inches into harder rock, such as limestone, dolomite and hard sandstone and a minimum of 18 inches into softer rock such as soft sandstone, siltstone, mudstone, and shale. The sides of the footing shall be poured in contact with the sides of the intact rock excavation; all fractured or loose rock shall be removed. Since rock removal can damage the structure of the formation making it potentially less resistant to scour, the bottom of footing elevation should be placed at the lowest of the following elevations:

- a) Top of footing at or below top of rock if rock will potentially be exposed by scour.

- b) Keyed 6 in. into the loadbearing hard rock layer or 18 in. into the loadbearing soft rock layer.

- c) 3 ft. below the total scour design flood depth (below frost line).

- d) Below the total scour check flood depth.

Spread footings on rock highly resistant to scour (i.e. granite and rhyolite) shall be either keyed a minimum of 6 inches into the rock or have steel dowels drilled and grouted into the rock. Contact Geotechnical section for recommendation on whether to key into rock or use dowels.

750.3.1.9 List of References

1. Lagasse, J.D., et al., 2012, Stream Stability at Highway Structures – Fourth Edition - Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 20 (HEC-20), Federal Highway Administration, Publication No. FHWA-HIF-12-004

2. AASHTO, 2007, Highway Drainage Guidelines, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

3. United States Water Resources Council, 1981, Guidelines for Determining Flood Flow Frequency, Bulletin #17B of the Hydrology Committee

4. Alexander, T.W. and Wilson, G.L., 1995, Technique for Estimating the 2 to 500 Year Flood Discharges on Unregulated Streams in Rural Missouri, USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4231

5. Southard, R.E., 2010, Estimation of the Magnitude and Frequency of Floods in Urban Basins in Missouri, USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5073

6. Brunner, G.W., 2010, HEC-RAS River Analysis System User’s Manual, US Army Corps of Engineers

7. Brunner, G.W., 2010, HEC-RAS River Analysis System Hydraulic Reference Manual, US Army Corps of Engineers

8. Warner, J.C., et al., 2009, HEC-RAS, River Analysis System Applications Guide, US Army Corps of Engineers

9. Barnes, H.H., 1967, Roughness Characteristics of Natural Channels, USGS Water-Supply Paper 1849

10. Arcement, G.L. & Schneider, V.R., 1984, Guide for Selecting Manning's Roughness Coefficients for Natural Channels and Flood Plains, Federal Highway Administration, Report No. FHWA-TS-84-204

11. Chow, V.T., Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw Hill Book Company, 1988, pp. 108-123

12. Schall, J.D., et al., 2012 Hydraulic Design of Highway Culverts, Third Edition - Hydraulic Design Series No. 5 (HDS-5), Federal Highway Administration, Publication No. FHWA-HIF-12-026,

13. FHWA, 1981, The Design of Encroachments on Flood Plains Using Risk Analysis - Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 17 (HEC-17), Federal Highway Administration

14. Arneson L.A., et al., 2012, Evaluating Scour at Bridges, Fifth Edition - Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 18 (HEC-18), Federal Highway Administration, Publication No. FHWA-HIF-12-003,

15. Keaton J.R. et al., 2012, Scour at Bridge Foundations on Rock, NCHRP Report 717, Transportation Research Board

16. Ettema R. et al., 2010, Estimation of Scour Depth at Bridge Abutments (Draft Final Report), NCHRP Report 24-20, Transportation Research Board.

750.3.2 Hydraulic Design Process

750.3.2.1 Overview

The hydraulic design process begins with the collection of data necessary to determine the hydrologic and hydraulic characteristics of the site. The hydraulic design process then proceeds through the hydrologic analysis stage, which provides estimates of peak flood discharges through the structure. The hydraulic analysis provides estimates of the water surface elevations required to pass those peak flood discharges. A scour analysis provides an estimate of the required depth of bridge foundations. A risk assessment is performed for all structures, and when risks to people, risks to property, or economic impacts are deemed significant, a least total economic cost analysis shall be performed to ensure the most appropriate and effective expenditure of public funds. Finally, proper documentation of the hydraulic design process is required.

The level of detail of the hydrologic and hydraulic analyses shall remain consistent with the site importance and with the risk posed to the highway facility and adjacent properties by flooding.

750.3.2.2 Data Collection

The first step in hydraulic design is collecting all available data pertinent to the structure under consideration. Valuable sources of data include the bridge survey; satellite imagery, aerial photography and various maps; site inspections; soil surveys; plans, surveys, and computations for existing structures; and flood insurance study data.

750.3.2.2.1 Bridge Survey

The bridge survey is prepared by district personnel and provides information regarding existing structures, nearby structures on the same stream, and streambed and valley characteristics including valley cross-sections along the centerline of the proposed structure, valley cross-sections upstream and downstream of the proposed structure, and a streambed profile through the proposed structure.

Location of the surveyed valley sections is an important factor in developing the best possible water surface profile model for the proposed structure. For this reason, inclusion of the bridge survey as an agenda item on an initial core team meeting to discuss appropriate location of the valley sections is recommended.

Bridge surveys are conducted in accordance with EPG 748.7 Bridge Reports and Layouts.

750.3.2.2.2 Photographs and Maps

Aerial photography, satellite imagery, USGS topographic maps, and county maps should be consulted to determine the geographic layout of the site. Aerial photographs, and satellite imagery in particular, can provide information on adjacent properties that may be subjected to increased risk of flood damage by the proposed structure, and may be available from the MoDOT Photogrammetry Section.

750.3.2.2.3 Site Inspection

A site inspection is a vital component of the hydrologic and hydraulic analyses, and is especially important for those sites subjected to risk of significant flood damage. A visit to the proposed site can provide the following information:

- selection of roughness coefficients

- evaluation of overall flow directions

- observation of land use and related flood hazards

- geomorphic observations (bank and channel stability)

- high-water marks

- evidence of drift and debris

- interviews with local residents or construction and maintenance personnel on flood history

Photographs taken during the site visit provide documentation of existing conditions and will aid in later determination of hydraulic characteristics.

750.3.2.2.4 Flood Insurance Study Data

If a Flood Insurance Study (FIS) has been performed for the community in which the structure is proposed, the FIS may provide an additional data source. The FIS may contain information on peak flood discharges, base flood elevations (BFE) water surface profile elevations, and information on regulatory floodways.

750.3.2.2.5 Data Review

After all available data has been compiled, the data should be reviewed for accuracy and reliability. Special attention should be given to explaining or eliminating incomplete, inconsistent or anomalous data.

750.3.2.3 Bridge Hydrologic Analysis

Peak flood discharges are determined by one of the following methods. If the necessary data is available, discharges should be determined by all methods and engineering judgment used to determine the most appropriate.

750.3.2.3.1 Historical USGS Stream Gage Data

See EPG 749.7 Historical USGS Stream Gage Data

750.3.2.3.2 NFIP Flood Insurance Study Discharges

See EPG 749.8 NFIP Flood Insurance Study Discharges

750.3.2.3.3 USGS Rural Regression Equations

See EPG 749.6.1 Rural Regression Equations.

750.3.2.3.4 USGS Urban Regression Equations

See EPG 749.6.2 Urban Regression Equations.

750.3.2.3.5 Other Methods

Other methods of determining peak flood discharges include the Corps of Engineers' HEC-1 and HEC-HMS hydrologic modeling software programs, the SCS TR-20 hydrologic modeling software program, and the SCS TR-55 Urban Hydrology for Small Watersheds method. See also EPG 749.9 Flood Hydrographs.

Use of these alternate methods should be limited to situations where the methods given above are deemed inappropriate or inadequate.

750.3.2.4 Hydraulic Analysis of Bridges

The Corps of Engineers Hydrologic Engineering Center's River Analysis System (HEC-RAS) shall be used to develop water surface profile models for the hydraulic analysis of bridges. Documentation on the use of HEC-RAS is available in references (6), (7), and (8).

Hydraulic design of bridges requires analysis of both the "natural conditions" and the "proposed conditions" at the site. In order to show that structures crossing a NFIP regulatory floodway cause no increase in water surface elevations, it is also necessary to analyze the "existing conditions."

For these reasons, water surface profile models for bridges shall be developed for three conditions:

- Natural conditions - Includes natural channel and floodplain, including all modifications made by others, but without MoDOT structures

- Existing conditions - Includes natural conditions and existing MoDOT structure(s)

- Proposed conditions - Includes natural conditions, existing MoDOT structures if they are to remain in place, and proposed MoDOT structure(s)

Backwater from another stream is determined by comparing the water surface elevations upstream of the structure for either existing conditions or proposed conditions to the corresponding water surface elevation for the natural conditions.

For bridges near a confluence with a larger stream downstream of the site, additional models may be required. The water surface profile and resulting backwater should be evaluated both with and without backwater from the larger stream. The higher backwater resulting from the proposed structure shall be considered to control.

The hydraulic model in HEC-RAS is based on an assumption of one-dimensional flow. If site conditions impose highly two-dimensional flow characteristics (i.e. a major bend in the stream just upstream or downstream of the bridge, very wide floodplains constricted through a small bridge opening, etc.), the adequacy of these models should be considered. A two-dimensional model may be necessary in extreme situations.

750.3.2.4.1 Design High Water Surface Elevation

The design high water surface elevation is the normal water surface elevation at the centerline of the roadway for the bridge freeboard design flood discharge. This elevation may be obtained using the slope-area method or from a "natural conditions" water surface profile.

750.3.2.4.2 Slope-Area Method

The slope-area method applies Manning's equation to a natural valley cross-section to determine stage for a given discharge. Manning's equation is given as:

- where:

- Q = Discharge (cfs)

- n = Manning's roughness coefficient

- A = Cross-sectional area (ft2)

- R = Hydraulic radius = A/P

- P = Wetted perimeter (ft)

- So = Hydraulic gradient (ft/ft)

In order to apply Manning's equation to a natural cross-section, the cross-section must be divided into sub-sections. The cross-section should be divided at abrupt changes in geometry and at changes in roughness characteristics.

For a given water surface elevation, the discharge can be determined directly from Manning's equation. Determination of the water surface elevation for a given discharge requires an iterative procedure.

The slope-area method should not be used with the roadway centerline valley cross-section to determine the design high water surface elevation when the centerline cross-section is not representative of the stream reach, such as when the new alignment follows or is very near the existing alignment. The centerline cross-section should also not be used when the centerline cross-section is not taken perpendicular to the direction of flow, such as when the alignment is skewed to the direction of flow or is on a horizontal curve. In these cases, an upstream or downstream valley cross-section should be used to determine the design high water surface elevation. The water surface elevation for an upstream or downstream valley cross-section can be translated to the roadway centerline by subtracting or adding, respectively, the hydraulic gradient multiplied by the distance along the stream channel from the valley cross-section to the roadway centerline.

A computer program is available to assist in making the slope-area calculations.

750.3.2.4.3 Roughness Coefficients

Roughness coefficients (Manning's "n") are selected by careful observation of the stream and floodplain characteristics. Proper selection of roughness coefficients is very significant to the accuracy of computed water surface profiles. The roughness coefficient depends on a number of factors including surface roughness, vegetation, channel irregularity, and depth of flow. It should be noted that the discharge in Manning's equation is inversely proportional to the roughness coefficient (e.g., a 10% decrease in roughness coefficient will result in a 10% increase in the discharge for a given water surface elevation).

It is extremely important that roughness coefficients in overbank areas be carefully selected to represent the effective flow in those areas. There is a general tendency to overestimate the amount of flow occurring in overbank areas, particularly in broad, flat floodplains. Increasing the roughness coefficients on overbanks will increase the proportion of flow in the channel, with a corresponding decrease in the proportion of flow on the overbanks.

References (9), (10), and (11) provide guidance on the selection of roughness coefficients.

750.3.2.4.4 Hydraulic Gradient (Streambed Slope)

The hydraulic gradient (So) is the slope of the water surface in the vicinity of the structure. It is generally assumed equal to the slope of the streambed in the vicinity of the structure. Note that the hydraulic gradient is typically much smaller than the valley slope used in the USGS regression equations. Hydraulic gradient is a localized slope, while valley slope is the average slope of the entire drainage basin.

Hydraulic gradient is determined by one of two methods, depending on drainage area:

- For drainage areas less than 10 mi2, the gradient is determined by fitting a slope to the streambed profile given on the bridge survey.

- For drainage areas greater than 10 mi2, the gradient is determined from USGS 7.5 minute topographic maps by measuring the distance along the stream between the nearest upstream and downstream contour crossings of the stream. The hydraulic gradient is then given by the vertical distance between contours divided by the distance along the stream between contours.

750.3.2.4.5 Overtopping Discharge and Frequency

The overtopping flood frequency of the stream crossing system - roadway and bridge - shall be determined if the overtopping frequency is less than 500-years. An approximate method of determining the overtopping discharge uses the slope-area method given above and setting the stage to the elevation of the lowest point in the roadway. A more accurate method involves using a trial-and-error procedure, adjusting the discharge in the HEC-RAS proposed conditions model until flow just begins to overtop the roadway. The overtopping frequency can then be estimated by linear interpolation from previously developed discharge-frequency data.

750.3.2.4.6 Waterway Enlargement

There are situations where roadway and structural constraints dictate the vertical positioning of a bridge and result in small vertical clearances between the low chord and the ground. In these cases, significant increases in span length provide small increases in effective waterway opening. It is possible to improve the effective waterway area by excavating a flood channel through the reach affecting the hydraulic performance of the bridge. This is accomplished by excavating material from the overbanks as shown in the figure below; enlargement of the channel itself is avoided where possible as excavation below ordinary high water is subject to 404 permit requirements.

A similar action may be taken to compensate for increases in water surface elevations caused by bridge piers in a floodway.

There are, however, several factors that must be accommodated when this action is taken.

- The flow line of the flood channel must be set above the ordinary high water elevation.

- The flood channel must extend far enough upstream and downstream of the bridge to establish the desired flow regime through the affected reach.

- Stabilization of the flood channel to prevent erosion and scour should be considered.

750.3.2.5 Scour Analysis

Current methods of analyzing scour depths are based mainly on laboratory experiment rather than on practical field data. The results should be carefully reviewed and engineering judgment used to determine their applicability to actual field conditions.

HEC-RAS includes the ability to calculate scour depths. The methods used to calculate those depths are based on the FHWA HEC-18 publication. Additional methods for abutment scour, scour in cohesive soils, scour in rock, and for scour in coarse bed streams not found in HEC-RAS are available in HEC-18. Rock scour information in HEC-18 is based on NCHRP Report 717.

750.3.2.5.1 Long Term Profile Changes - Aggradation and Degradation

Long term profile changes result from aggradation or degradation in the stream reach over time. Aggradation involves the deposition of sediment eroded from the channel and banks upstream of the site. Degradation involves the lowering or scouring of a streambed as material is removed from the streambed and is due to a deficit in sediment supply upstream. Aggradation and degradation are generally the result of changes in the energy gradient of the stream.

Aggradation and degradation over the life of a structure are difficult to predict. These long term profile changes are typically the result of human activities within the watershed including dams and reservoirs, changes in land use, gravel mining and other operations. HEC-18 and HEC-20 provide more information on predicting long term profile changes. Comparison of channel bottom elevations shown on plans for existing bridges to current survey data may be informative.

750.3.2.5.2 Contraction Scour

Contraction scour is generally caused by a reduction in flow area, such as encroachment on the floodplain by highway approaches at a bridge. Increased velocities and increased shear stress in the contracted reach result in transport of bed material. Contraction scour typically occurs during the rising stage of a flood event; as the flood recedes, bed material may be deposited back into the scour hole, leaving no evidence of the ultimate scour depth.

Contraction scour may be one of two types: live-bed contraction scour or clear water contraction scour. Live-bed scour occurs when the stream is transporting bed material into the contracted section from the reach just upstream of the contraction. Clear-water scour occurs when the stream is not transporting bed material into the contracted section. The type of contraction scour is determined by comparing the average velocity of flow in the channel or overbank area upstream of the bridge opening to the critical velocity for beginning of motion of bed material.

Live-Bed Contraction Scour - Live-bed contraction scour depths can be determined using the equations in FHWA HEC-18.

The upstream cross-section is typically located either one bridge opening length or the average length of constriction upstream of the bridge. This is consistent with the required location of the approach cross-section in both HEC-RAS and WSPRO.

Clear Water Contraction Scour - Clear-water contraction scour depths can be determined using the equations in FHWA HEC-18.

750.3.2.5.3 Local Scour

Local scour involves removal of material from around piers, abutments and embankments and is caused by increased velocities and vortices induced by the obstruction to flow. As with contraction scour, bed material may be deposited back into the scour holes as floodwaters recede.

Pier scour and abutment scour are considered two distinct types of local scour.

Pier Scour - Pier scour depths can be determined using the equation found in FHWA HEC-18.

The HEC-18 Pier Scour Equation is based on the Colorado State University (CSU) equation. The equation is best suited for non-cohesive soils, but has been used for cohesive soils. Additional equations are provided in HEC-18 for cohesive soils, coarse bed materials and erodible rock.

The pier scour depth is limited to a maximum of 2.4 times the pier width for Froude numbers less than or equal to 0.8, and a maximum of 3.0 times the pier width for Froude numbers greater than 0.8.

The pier width used in the equations is that projected normal to the direction of flow. Piers should be skewed to minimize this width. The effect of debris should be considered in evaluating pier scour by considering the width of accumulated debris in determining the pier width used in the above equations.

For multiple columns with a spacing of 5 diameters or more, the total pier scour is limited to a maximum of 1.2 times the scour depth calculated for a single column. For multiple columns spaced less than 5 diameters apart, a "composite" pier width that is the total projected width normal to the angle of attack of flow should be used. For example, for three 6 ft. diameter columns spaced at 25 ft. apart, the pier width is somewhere between 6 ft. and 18 ft. (three times six feet), depending on the angle of attack.

Top width of pier scour holes, measured from the pier to the outer edge of the scour hole, can be estimated as 2.0 x the scour hole depth, ys.

Abutment Scour - Abutment scour depths can be determined using the equations found in FHWA HEC-18.

The first equation, is the Froelich Abutment Scour Equation.

The HIRE Abutment Scour Equation, is recommended when the ratio of projected abutment length, L', to flow depth, ya, is greater than 25.

HEC-18 also provides another approach to calculating abutment scour which is based on NCHRP Report 24-20.

750.3.2.5.4 Rock Scour

Since scour in rock is mainly an issue for spread footings, and the number of spread footings used in or near streambeds is limited, use the following procedure to request rock scour parameters to prevent unnecessary geotechnical sampling and testing.

- a) Spread footings should be specified on the request for soil properties form when soundings (borings) are requested. By default for spread footings and retaining walls, rock erodibility is automatically checked for investigation of rock parameters for scour by the Geotechnical Section.

- b) The foundation investigation geotechnical report should provide erodibility index numbers and indicate if scour numbers will be provided for further recommended evaluation. Alternatively, if rock scour is determined to not be a concern it should be noted on the report.

- c) If spread footing option requires further evaluation, Bridge Division should follow-up with the Geotechnical Section and request scour numbers when they are scheduled to be available. The testing used to determine scour numbers may require 2 weeks.

750.3.2.5.5 Total Scour

All the above types of scour are considered in determining proper depth of bridge foundations. The total scour is obtained by adding the individual scour components.

Provide justification if scour analysis is not performed (slope protection can eliminate the need for abutment scour calculations, etc.)

750.3.3 Documentation of Hydraulic Design

Documentation is viewed as the record of reasonable and prudent design analysis based on the best available technology. Documentation should be an on-going process throughout the design and life of the structure.

Proper documentation achieves the following:

- Protects MoDOT and the designer by proving that reasonable and prudent practices were used (be careful to state uncertainties in less than specific terms)

- Identifies site conditions at time of design

- Documents that practices used were commensurate with the perceived site importance and flood hazard

- Provides continuous site history to facilitate future construction

At a minimum, the following documentation of the hydraulic design is to be archived:

- Bridge Survey Report form, associated plan and profile sheets

- Bridge Hydraulics and Scour Report or Culvert Hydraulics Report

- Any computation sheets used in the hydrologic and hydraulic analyses

- Program input/output files from water surface profile model(s), HY-8, HEC-RAS or other computer programs.

- Input and output data. Computer program input files must be reproducible from the data provided.