127.2 Historic Preservation and Cultural Resources

Why is Missouri Department of Transportation concerned with historic preservation and cultural resources? MoDOT strives to balance historic preservation regulations and concerns with the task of planning, designing, constructing, and maintaining the state’s complex transportation infrastructure. MoDOT’s Historic Preservation (HP) staff works to identify potential conflicts between the two and to help resolve them in the public interest. The HP staff ensures that no MoDOT job is denied federal funds or permits due to lack of compliance with historic preservation regulations. MoDOT makes every effort to comply with federal and state historic preservation legislation and regulations, and address citizen concerns, while being a good steward of Missouri's historic and prehistoric resources.

The guidance in EPG 127.2 explains how MoDOT complies with Section 106 for projects in the Statewide Transportation Improvement Plan. MoDOT also has been delegated oversight responsibilities by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for Section 106 compliance for FHWA-funded projects conducted by the Local Public Agencies (LPA). MoDOT’s Section 106 guidance for LPA is provided in EPG 136.6.4.1 Section 106 (Cultural Resource) Compliance.

Contents

- 1 127.2.1 Definitions

- 2 127.2.2 Historic Preservation Staff

- 3 127.2.3 Historic Preservation Regulations and Laws

- 4 127.2.4 What Jobs Require Section 106 Compliance

- 5 127.2.5 Approximate Timelines for Section 106 Compliance

- 6 127.2.6 How does the District Initiate Section 106 Compliance

- 7 127.2.7 Confidentiality of Archaeological Site Locations

- 8 127.2.8 Artifacts and Features

- 9 127.2.9 Construction Inspection Guidance

- 10 127.2.10 Historic Bridge Information

- 11 127.2.11 Early Acquisition of Right-of-Way and Disposal of Uneconomic Remnants

127.2.1 Definitions

Agreement Documents: Agreement documents include Memorandums of Agreement (MOA), Programmatic Agreements (PA) and Memorandums of Understanding (MOU). These are negotiated and signed legal documents among agencies and other consulting parties. Failure to comply with the terms of an Agreement Document may result in the cancellation of the agreement (potentially jeopardizing compliance with the Section 106 process) and may result in one of the parties suing the others for non-compliance with Section 106.

- MOAs are appropriate to record the agreed upon resolution for a specific undertaking with a defined beginning and conclusion, where adverse effects are understood. MOAs may identify the processes to be used but typically focus more on how project impacts on cultural resources will be handled. The MOA may specify avoidance, preservation in place, or mitigation activities for a resource and often has a detailed treatment plan attached that details the activities that must occur.

- PAs are appropriate for multiple or complex federal undertakings where 1) effects to historic properties cannot be fully determined in advance, 2) for federal agency programs, 3) for routine management activities by an agency, or 4) to tailor the standard Section 106 process to better fit in with agency management or decision making. PAs may identify how specific resources may be treated, but they focus more on the Section 106 responsibilities, processes and timelines to be used and the parties to be involved in the process.

- MOUs are less common and typically are agreements between agencies about funding and responsibilities.

Area of Potential Effects: the geographic area or areas within which an undertaking may directly or indirectly cause alterations in the character or use of historic properties, if any such properties exist. The area of potential effects is influenced by the scale and nature of an undertaking and may be different for different kinds of effects caused by the undertaking.

Consulting Parties: The Section 106 regulation states, “the section 106 process seeks to accommodate historic preservation concerns with the needs of Federal undertakings through consultation.” The parties that are part of the consultation process may include the State Historic Preservation Officer, Native American Tribes, communities and other interested parties with a demonstrated interest in the cultural resources or project (e.g. private foundations, not for profit organizations).

Cultural Resources: These are defined as the collective evidence of the past activities and accomplishments of people, such as archaeological sites, buildings, objects, features, locations, and structures with scientific, historic, and cultural value.

Effect: The alteration to the characteristics of a historic property qualifying it for inclusion in or eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places. “Adverse effects” are those that diminish characteristics qualifying a property for inclusion in the National Register.

Historic Property: A Historic property is any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object included in, or eligible for inclusion in, the National Register of Historic Places maintained by the Secretary of the Interior. This term includes artifacts, records, and remains that are related to and located within such properties. The term includes properties of traditional religious and cultural importance to an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and that meet the National Register criteria

National Register of Historic Places: This is the nation's official list of historic places worthy of preservation that was authorized under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. It is an important planning tool under several preservation laws. Properties that can be listed include districts, archaeological sites, buildings, structures, or objects that are significant in American history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, and culture. The National Register is administered by the National Park Service, which is part of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Phase I Survey: The Phase I Survey is a reconnaissance survey to identify archaeological sites and buildings in a project’s area of potential effects. Systematic shovel test pit sampling is employed to locate archaeological sites. If potentially significant archaeological sites are identified in the survey, a Phase II Site Testing is generally recommended.

Phase II Archaeological Site Testing: The purpose of Phase II testing is to collect sufficient archaeological data to determine historical and cultural significance of archaeological materials located during Phase I survey and to determine the site’s eligibility for listing on the National Register and what the project’s effect will be upon it.

Phase III Mitigation/Data Recovery: Phase III archaeological data recovery is specifically tailored to recover the data that will be destroyed by the project. It is a highly-intensive version of Phase II, incorporating significantly more excavation, testing, mapping, and analysis of cultural material found on the site.

Section 106: Provision in the National Historic Preservation Act that requires federal agencies to consider the effects of proposed undertakings on properties listed or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. (16 U.S. Code §470f; 36 C.F.R. Part 800)

Section 4(f): Section 4(f) refers to the original section within the U.S. Department of Transportation Act of 1966 which provided for consideration of park and recreation lands, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites during transportation project development. The law, now codified in 49 U.S.C. §303 and 23 U.S.C. §138, applies only to the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) and is implemented by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration through the regulation 23 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 774.

Section 4(f) Resource: These include publicly owned public parks, recreation areas, and wildlife or waterfowl refuges, or any publicly or privately-owned historic site listed or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). If a site is determined not to be listed on or eligible for listing on the NRHP, FHWA still may determine that the application of Section 4(f) is appropriate when an official (such as the Mayor, president of the local historic society, etc.) formally provides information to indicate that the historic site is of local significance.

Undertaking: A Federal undertaking is a project, activity, or program either funded, permitted, licensed, or approved by a Federal Agency.

127.2.2 Historic Preservation Staff

The MoDOT Historic Preservation staff is part of the Central Office Design Division. Staff archaeologists handle issues regarding archeological resources, while the architectural historians handle issues involving buildings, structures, culverts and bridges. The historic preservation staff also a computer graphics specialist who modify project plans for submittal to other agencies. The MoDOT historic preservation staff conducts cultural resources investigations, prepares recommendations based on these investigations, and reviews cultural resources work done by consultants. The Historic Preservation staff is also available to assist with public interaction including providing presentations or displays at public meetings or preparing brochures or handouts.

127.2.3 Historic Preservation Regulations and Laws

The National Historic Preservation Act is the premier law in a series of laws that govern historic preservation. Additional laws that have a historic preservation aspect that MoDOT also needs to comply with include, but not limited to, are:

- The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is legislation establishing national environmental policy and goals for the protection, maintenance, and enhancement of the environment. NEPA established the President’s Council on Environmental Quality and required that federal agencies establish procedures for evaluating the impacts of their actions on the natural and human environment. Federal agencies are required to involve stakeholders in the NEPA process.

- The Native American Grave and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) requires federal agencies to consult with the appropriate Native American Tribes prior to the intentional excavation of human remains and funerary objects. The regulations establish a process for determining the rights of lineal descendants and Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations to certain Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony with which they are affiliated.

- American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) is a US federal law and a joint resolution of Congress that was passed in 1978. It was created to protect and preserve the traditional religious rights and cultural practices of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts and Native Hawaiians. These rights include, but are not limited to, access of sacred sites, repatriation of sacred objects held in museums, freedom to worship through ceremonial and traditional rites, and use and possession of objects considered sacred.

- Executive Orders 13007 (Indian Sacred Sites) was issued in 1996, directing federal agencies, to the extent practicable and allowed by law, to allow Native Americans to worship at sacred sites located on federal property and to avoid adversely affecting the physical integrity of such sites.

- Executive Order 13287 (Preserve America) 13287 was issued in 2003, directing federal agencies to actively advance the protection, enhancement, and contemporary use of the historic properties owned by the federal government. It also encouraged agencies to establish partnerships with state, tribal, and local governments and the private sector to use these resources for economic development (e.g., tourism) and other public benefits.

127.2.3.1 Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) encourages the identification and preservation of cultural resources through partnership with federal, state, tribal, and local governments. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), as an agency of the federal government, has responsibilities under the NHPA. These tasks are codified in a series of laws and policies. Much of the responsibility to follow these laws has been delegated by the FHWA to MoDOT.

Section 106 of the NHPA requires that MoDOT consider the potential impacts that any federally funded or permitted project may pose to significant cultural resources. Cultural resources include archaeological sites, buildings, structures (e.g., bridges), objects, and districts. The significance of a cultural resource is evaluated by applying a set of criteria that are set forth by the National Register of Historic Places. Cultural resources that meet the criteria of eligibility for listing, or already listed, on the National Register are referred to as "historic properties." Failure to obtain Section 106 clearance could jeopardize federal funding and permits for a project, which could result in project delays. Section 106 compliance requires MoDOT to:

- Initiating Section 106 – Identify who should participate in the review. Consulting parties may include the State (or Tribal) Historic Preservation Officer, the local government, an applicant for federal assistance (if one is involved) and interested federally recognized Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations. Historic preservation organizations and others with an interest in the preservation outcomes of the project or those with a legal or economic interest may also be invited to join consultation. The agency also plans how it will involve the public.

- Identify Historic Properties – Establish the project’s area of potential effect (APE) and determine if any cultural resources within the APE are historic properties. If no historic properties are present, or if those present will not be affected by the project, the review may conclude here.

- Assess Adverse Effects – Determine how historic properties might be affected by the project and whether any of those effects would be considered adverse. “Adverse effects” are those that diminish characteristics qualifying a property for inclusion in the National Register. If there are no potential adverse effects to a historic property, the review may conclude here.

- Resolve Adverse Effects – Explore measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse effects to historic properties and reach agreement with the State Historic Preservation Officer on measures to resolve them.

Section 106 encourages, but does not mandate, the preservation of historic properties. The goal of Section 106 is to ensure that preservation values and the views of consulting parties and the public are factored into the planning process for all federally funded or permitted projects. It provides assurance that agencies will assume responsibility and public accountability for their decisions when dealing with cultural resources, and specifically historic properties.

127.2.3.1.1 Tribal Consultation

Federal agencies are required to consult on a “government-to-government” basis with federally-recognized Indian tribes and nations on projects receiving federal funds or requiring federal permits. The federal government’s unique relationship with Indian tribes is embodied in the U.S. Constitution, treaties, court decisions, federal statutes and executive orders. Tribal consultation for MoDOT projects is primarily conducted through the Missouri Division of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

FHWA consults with federally-recognized Indian tribes with ancestral, historic, and ceded land connections to Missouri. Consultation with tribes is intended to facilitate avoiding or minimizing project impacts to cultural resources that a tribe considers of historical or religious significance. More information on Tribal Consultation is available on MoDOT’s Historic Preservation’s Tribal Consultation webpage.

127.2.3.1.2 Consulting Parties and Public Consultation

Consultation is the process of seeking, discussing and considering the views of other participants, and, where feasible, seeking agreement with them on matters arising in the Section 106 process. The Consulting Parties can include Federal Agencies (FHWA, Forest Service, National Park Service, etc.), the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), Project applicants (MoDOT and LPAs), interested Tribes, Local governments, the public with a demonstrated interest in the undertaking. FHWA and MoDOT work with the SHPO to identify consulting parties and invite them to participate in consultation. Consulting parties help FHWA and MoDOT make decisions. Because they often live in a community, consulting parties can help identify properties that are eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, especially properties that are associated with historic events or individuals that might not be easily determined without extensive research. More information on Consultation is on MoDOT’s Historic Preservation’s Consultation webpage.

127.2.3.2 Section 4(f)

Section 4(f) was originally stipulated in the Department of Transportation Act of 1966 (Pub. L. 89-670, 80 Stat. 931). It is now codified at 23 U.S.C. § 138 and 49 U.S.C. § 303, although it is still commonly referred to as “Section 4(f).” Potential adverse effects to certain kinds of historic properties that are identified during the Section 106 process may require the preparation of a Section 4(f) evaluation.

Section 4(f) requirements stipulate that FHWA and other DOT agencies cannot approve the use of land from publicly owned parks, recreational areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, or public and private historical sites unless the following conditions apply:

- There is no feasible and prudent avoidance alternative to the use of land; and the action includes all possible planning to minimize harm to the property resulting from such use;

- OR

- FHWA determines that the use of the property will have a de minimis impact.

Additional information related to Section 4(f) can be found in FHWA’s Section 4(f) Policy Paper or the Section 4(f) Tutorial.

When Section 4(f) properties are present, district Design staff will be requested to provide specific information to assist the Historic Preservation staff to complete the Section 4(f) evaluations:

- Bridge Programmatic: the district Design staff fills out Sections A, B and E (project description, Purpose & Need, alternatives) of the Programmatic Section 4(f) Evaluation Form.

- Historic De Minimis: if it is contingent upon a do not disturb (DND), or a job special provision (JSP), the district Design staff works with the HP staff to delineate the DND or draft the JSP.

- Individual Evaluation: the district Design staff provides to the HP staff description of the proposed action including purpose & need, impacts to the 4(f) property, alternatives (including cost estimates), public involvement and coordination, sometimes they need to provide additional assistance with the least overall harm analysis.

127.2.3.3 Missouri Burials Laws

There are two state laws that involve projects encountering human burials. The Unmarked Human Burials law (RSMo 194) addresses situations where activities impact prehistoric burials and previously unrecognized historic burials. The Cemeteries law (RSMo 214) addresses project impacts to cemeteries and historic burials that are marked by headstones, particular kinds of vegetation or local folklore. If burials or human skeletal remains are encountered during construction, construction in that area must cease and Historic Preservation Staff immediately contacted.

127.2.3.3.1 Missouri Unmarked Human Burials Law

If human skeletal remains are encountered during construction, their treatment will be handled in accordance with Sections 194.400 to 194.410, RSMo, as amended. When human remains are encountered, the Contractor shall first stop all work within a 50-ft. radius of the remains, and secondly, shall notify the MoDOT Construction Inspector and/or Resident Engineer who will contact the Historic Preservation section. Historic Preservation staff will in turn notify the local law enforcement (to ensure that it is not a crime scene) and the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) as per RSMo 194 or to notify SHPO what has occurred and that it is covered by Missouri’s Cemeteries Law, §§ 214. RSMo. If the contractor is unable to contact appropriate MoDOT staff, the contractor shall initiate the involvement by local law enforcement and the SHPO. A description of the contractor’s actions will be promptly made to MoDOT.

If the human remains are prehistoric, the agency must consult with Indian tribes who have with ancestral, historic, and ceded land connections to the area in which the remains are located to determine the appropriate treatment of the remains. Tribal consultation may result in the conclusion that the remains should be preserved in place and construction plans changed to facilitate their preservation.

127.2.3.3.2 Missouri Cemetery Law

Missouri’s Cemeteries Law (Chapter 214. RSMo) requires that the local Circuit Court be notified whenever marked human remains are encountered with the court assuming jurisdiction of the remains if a next-of-kin cannot be located. The process also begins with the MoDOT Historic Preservation Section being notified immediately of the presence of a known or suspect grave site. The MoDOT Historic Preservation Section will notify MoDOT Chief Council’s Office CCO), who then contacts the court officials. Under the direction of CCO and the Circuit Court, an undertaker or archaeologist will remove the remains with the remains moved to a new location. The courts may require that MoDOT attempt to notify relatives of the deceased through various forms of the media (typically local newspapers).

Sections of Chapter 214, RSMo that have applied to MoDOT projects are:

- 214.041 – Construction of roads prohibited in cemetery—exceptions: “No road shall be constructed in any cemetery over a burial lot in which dead human remains are buried. Temporary access routes over burial lots may be used in the operation or maintenance of the cemetery or used in the construction of cemetery improvements or features. This section shall not apply to private or family cemeteries, as described in section 214.090.”

- 214.131 – Tombstones, fences, destroying or mutilating in abandoned family or private cemetery, penalty--abandoned or private burying ground, defined: “Every person who shall knowingly destroy, mutilate, disfigure, deface, injure or remove any tomb, monument or gravestone, or other structure placed in any abandoned family cemetery or private burying ground, or any fence, railing, or other work for the protection or ornamentation of any such cemetery or place of burial of any human being, or tomb, monument or gravestone, memento, or memorial, or other structure aforesaid, or of any lot within such cemetery is guilty of a class A misdemeanor. For the purposes of this section and subsection 1 of section 214.132, an "abandoned family cemetery" or "private burying ground" shall include those cemeteries or burying grounds which have not been deeded to the public as provided in chapter 214, and in which no body has been interred for at least twenty-five years.”

127.2.4 What Jobs Require Section 106 Compliance

Any job that receives Federal funds and permits, and involves:

- 1. ground disturbance within existing or proposed right-of-way or easements;

- 2. modifications to a bridge or culvert; and/or

- 3. destroys, relocates, or encroaches upon a building(s) or other features on a property, including sidewalks, fences, gateposts, entrance gates, and walls that may be contemporary with the building.

These actions may be associated with initial highway construction, maintenance, or subsequent improvement activities. Even if a project plan does not include these actions, later contractor or maintenance tasks could meet one of these criteria. It is imperative that the Historic Preservation Section be involved in project determinations about cultural resources and be notified if cultural resources are encountered within job limits during construction or on highway property in general. The Section 106 compliance for many of these projects can be handled with the Minor Highway Project Programmatic Agreement.

127.2.5 Approximate Timelines for Section 106 Compliance

When the project’s footprint has been established and the district has received landowner permission the field investigations can begin. The end point is when MoDOT is going to request the release of federal funds. The Federal Highway Administration requires Section 106 and NEPA to be completed to release the federal funds. This is usually the PS&E date unless federal funds are being used to purchase property; then it’s the A-date. To guarantee that there is no potential for a project to be pulled from the letting schedule the Section 106 and NEPA processes needs to start 18 months before the A-date.

- Jobs requiring new right-of-way/easements and where no historic properties are found or adversely affected, it will take approximately 3 months to complete the Section 106 process.

- Archaeological sites that need Phase II testing can add 1 to 3 months to the process – the timeline to compete the Section 106 process is 4-6 months.

- An adversely affected historic property will take an additional 4-6 months to negotiate and draft an agreement document (Memorandum of Agreement or Programmatic Agreement); the agreement document needs to be executed before NEPA is approved – the timeline to complete the Section 106 process is 8-12 months.

- The mitigation efforts to resolve the adverse effects upon a historic property as laid out in the agreement document stipulations include “field” mitigation efforts that need to be completed before the project can be advertised for construction bids (for example, excavations at archaeological sites, bridge photography, etc.). These field mitigation efforts can take 1-6 months to complete – the timeline to complete the Section 106 process is 9-18 months.

- If a project has an adverse effect on a historic property that is also a Section 4(f) property, a Section 4(f) Evaluation will need to be completed. Bridges have a nationwide programmatic Section 4(f) evaluation, which streamlines the process. If an Individual Section 4(f) Evaluation is required, anticipate that the process will take 12-15 months. Some portions of the Section 4(f) can be completed concurrently with the Section 106 consultation and resolution of adverse effects. The use of a Section 4(f) property cannot be approved by FHWA until the Section 4(f) Evaluation and the Section 106 process is completed.

- For a Design-Build Project, if a historic property is identified in the area of potential effects and an effect determination can’t be made due to lack of a design or a commitment can’t be made to avoid the historic property, an executed Programmatic Agreement will be required to advance the Section 106 process and to complete the NEPA evaluation.

127.2.6 How does the District Initiate Section 106 Compliance

The Section 106 process is initiated through the Request for Environmental Services (RES) for MoDOT projects or the Request for Environmental Review (RER) for LPA projects. Early involvement by MoDOT’s Historic Preservation (HP) staff provides an opportunity to identify and attempt to avoid adverse effects to historic properties that will minimize the time and cost of addressing Section 106 concerns during project development.

The submission by the Historic Preservation Section to the SHPO for project clearance minimally requires the project footprint on a topographic map. Most submissions also require a set of the project plans provided electronically for our graphic support staff to annotate with the results of our investigation. Photographs of a project area or specific resources (most often buildings or bridges) also may be requested from the district.

It is the district’s responsibility to contact the landowner or tenant to obtain the right of ingress for Historic Preservation staff to conduct a cultural resources survey. The project manager should verify with the historic preservation and environmental staff to verify if there are parcels that access is not required. The project manager provides a written list (e-mail is acceptable) of landowners with their phone number, permission status (ingress allowed, denied, or unknown) to the archaeologist or architectural historian handling the job. A sample letter requesting permission and a brochure showing a typical survey are provided. For any specific questions by a landowner, MoDOT historic preservation staff will make follow-up contacts.

- During the Location/Conceptual Stage, the HP staff should be consulted to determine if the project is a Section 106 undertaking, and if so, initiate the Section 106 process. The Section 106 process can be completed at this stage for certain projects that are considered “Minor Highway Projects” as per executed agreement documents. A change of the scope (e.g., type of project, later addition of right-of-way and/or easements, etc.) may remove a project from an earlier finding under this PA.

- During the Preliminary Plans Stage the HP staff should establish the APE, identify historic properties, assess the project’s effects upon them, resolve any adverse effects, and obtained SHPO’s concurrence with MoDOT’s finding (i.e., the standard Section 106 process).

- o To start the Section 106 process, the Historic Preservation section needs a footprint to survey (i.e., the maximum area consisting of new and existing right-of-way and temporary/permeant easements) and landowner permission.

- ▪ The “maximum footprint” should be larger enough to allow for adjustments during the design process and should include any known or planned offsite activity locations (e.g., borrow sites, staging areas, haul roads, burn pits and spoil sites, etc.).

- ▪ After the district has initiated landowner contact, HP staff can make follow-up calls if a property owner has specific questions, requests, or concerns.

- By the Right of Way Plans Stage, HP staff should have completed the standard Section 106 process (the preferred method) or notified FHWA and SHPO that a “Phased” Section 106 process is being used.

- o The “Phased Section 106 process is used when access to enough property is restricted to prevent a standard investigation to complete the Section 106 process before the ROW stage of project development. This allows the release of Federal funds for the purchase of properties with MoDOT making a commitment to complete the Section 106 process, which might lead to selling previously acquired property and the purchase of additional property in order to avoid an adverse effect to a historic property determined later in the project development process.

- o An Acquisition Authority (A-Date) for property acquisition can be approved upon SHPO accepting the initial Phased Section 106 submittal or by SHPO not responding within 15 days of their having received the submittal and the NEPA documentation is completed.

- By the completion of the Final Design Stage, the “Phased” Section 106 process should be completed, if being used, and any required agreement document has been executed.

- o Stipulations in the agreement document that need to be finished before construction need to be completed by the PS&E date.

- o Job Special Provisions (JSP) – Some jobs may require a JSP to the construction contract to guarantee that commitments made in the Section 106 agreement document or NEPA documentation to protect cultural resources from collateral damage that may occur during construction or carried out (e.g., monitoring construction, avoidance of certain areas within the job boundaries, etc.). The HP staff will draft the job special provisions with assistance from the district design staff.

The release of Federal funds by FHWA requires that the Section 106 process has been completed (i.e., the presence of historic properties and project effects upon any historic property(s) has been completed and SHPO has concurred with the finding).

127.2.7 Confidentiality of Archaeological Site Locations

Some information, such as the location of archaeological sites, may be subject to the provisions of Section 304 of the NHPA. Section 304 allows the applicable Lead Federal Agency to withhold from disclosure to the public, information about the location, character or ownership of a historic property if the applicable Lead Federal Agency determines that disclosure may: 1) cause a significant invasion of privacy, and 2) risk harm to the historic property. Archaeological site locations are not included in displays for public meetings and public hearings or otherwise disclosed to the general public. It is required that inquiries regarding archaeological site locations be forwarded to the Historic Preservation Section for response.

Information about historic properties All actions stipulated in this MOA, where necessary, will be consistent with the requirements of Section 304 of the NHPA.

127.2.8 Artifacts and Features

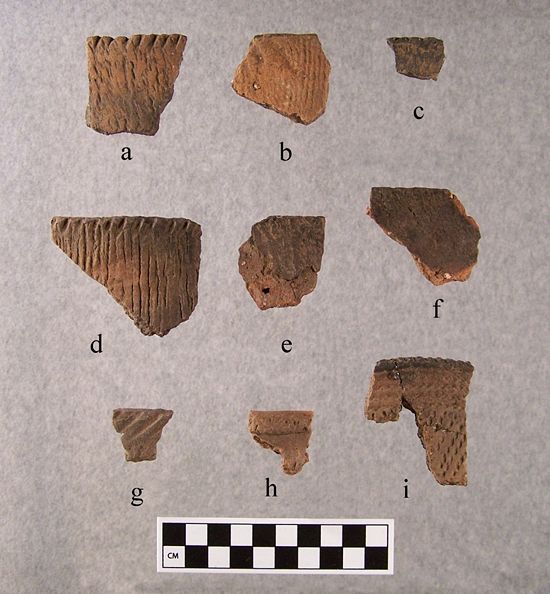

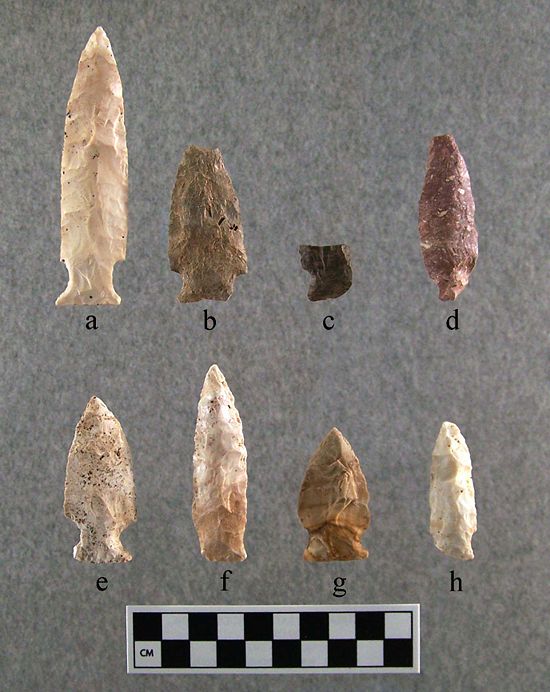

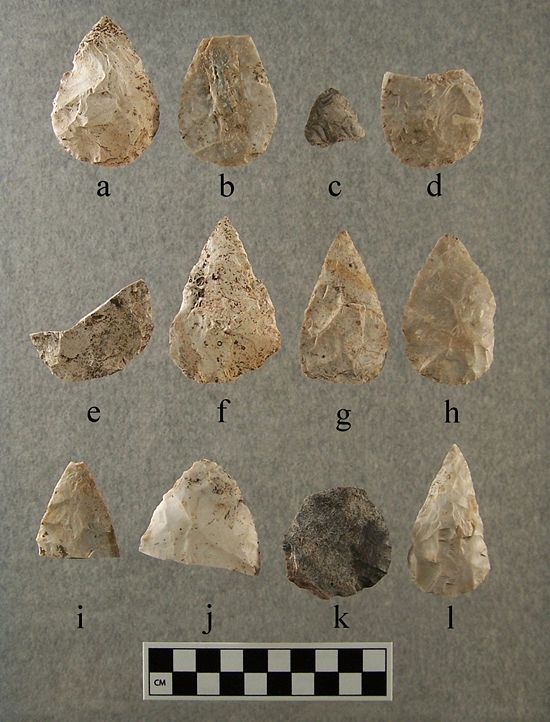

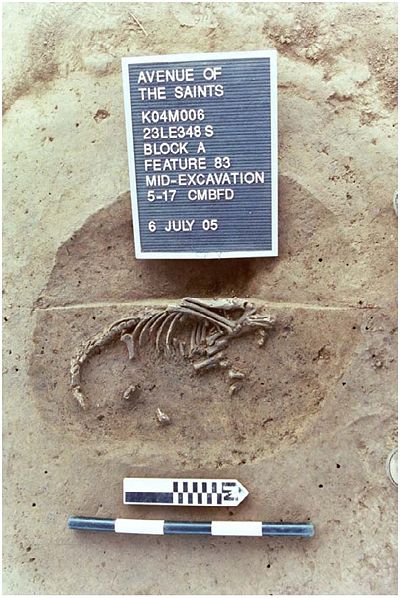

Prehistoric artifacts may consist of stone tools such as "arrow heads", flakes of chert from the manufacture of tools, pottery, bone or mussel shell concentrations. Sometimes artifacts will appear in a "feature" such as a hearth or storage pit that may include a distinct outline, charcoal, and mottled soils. Historic artifacts may include bottles, broken china, nails, window glass and features such as old wells, cisterns, foundations, root cellars or privy pits. When in doubt whether or not artifacts found during construction constitute an archaeological site, MoDOT Historic Preservation staff is available to examine the finds and determine if further investigation is warranted. If the artifacts indicate an important archaeological site, HP staff will work with construction personnel to avoid or minimize disruption to the project. Sample artifact types are illustrated below.

As noted above, MoDOT archaeologists will work with project personnel to avoid or minimize disruption to the project while satisfying Section 106 requirements. Failure to report a find during construction can result in adverse publicity for MoDOT, create greater delays for the project as other regulatory agencies may become involved, and can risk federal funding on the project.

Examples of Prehistoric Artifacts (from the Avenue of the Saints Project)

Examples of Historic Artifacts (from the Mississippi River Bridge and Poplar Street Bridge projects)

Examples of Prehistoric Features (from the Avenue of the Saints Project)

Examples of Historic Features (from the Mississippi River Bridge and Poplar Street Bridge projects)

127.2.9 Construction Inspection Guidance

Mitigation by data recovery is usually completed prior to construction if the presence of cultural resources is known. If artifacts are discovered during construction activities, the Historic Preservation section must be immediately notified. This will allow an inspection of the site by MoDOT HP staff to determine if further investigation is necessary before construction activities continue.

Sec. 107.8.2 and Sec. 203.4.8 of the Missouri Standard Specifications for Highway Construction require the contractor to take steps to preserve any such artifacts that may be encountered and to notify the MoDOT Construction Inspector or Resident Engineer of their presence. If it is necessary to discontinue operations in a particular area to preserve such objects, this section of the specifications is basis for a work suspension. In order to ensure compliance with applicable state laws, the MoDOT Construction Inspector or Resident Engineer cannot release remains or artifacts or allow the contractor to disturb the area within the 50-ft. buffer space around these discovered items, until after consultation with MoDOT HP staff and until after all applicable requirements from FHWA or SHPO have been addressed.

127.2.9.1 Cultural Resources Encountered During Construction

If cultural resources are encountered during construction, the contractor shall immediately stop all work within a 50-foot buffer around the limits of the resource and shall not resume without specific authorization from a MoDOT Historic Preservation Specialist. The contractor shall notify the MoDOT Resident Engineer or Construction Inspector, who shall contact the MoDOT HP within 24 hours of the discovery. MoDOT HP shall contact FHWA and SHPO within 48 hours of learning of the discovery and provide an evaluation of the resource and reasonable efforts to see if it can be avoided. FHWA shall make an eligibility and effects determination based upon the preliminary evaluation and consul with MoDOT, and SHPO a minimize or mitigate any adverse effect. FHWA will notify the Council and any tribes that might attach religious and/or cultural significance to the property within 48 hours of this determination. FHWA shall take into account Council and Tribal recommendations regarding the eligibility of the property and proposed actions, and direct MoDOT to carry out the appropriate actions. MoDOT will provide FHWA and SHPO with a report of the actions when they are completed. FHWA shall provide this report to the council and the tribes.

127.2.9.2 Human Remains Encountered During Construction

If human remains are encountered during construction, the contractor shall immediately stop all work within a 330-foot radius of the remains and shall not resume without specific authorization from MoDOT HP Staff, and either the SHPO or the local law enforcement officer, whichever party has jurisdiction over and responsibility for such remains. The contractor shall notify the MoDOT Construction Inspector and/or Resident Engineer who will contact the MoDOT HP section within 24 hours of the discovery. MoDOT HP staff will immediately notify the local law enforcement (to ensure that it is not a crime scene) and the SHPO as per RSMo 194 or to notify SHPO what has occurred and that it is covered by Missouri’s Cemeteries Law, §§ 214. RSMo. MoDOT HP staff will notify FHWA that human remains have been encountered within 24 hours of being notified of the find. If, within 24 hours, the contractor is unable to contact appropriate MoDOT staff, the contractor shall initiate the involvement by local law enforcement and the SHPO. A description of the contractor’s actions will be promptly made to MoDOT. FHWA will notify any Indian tribe that might attach cultural affiliation to the identified remains as soon as possible after their identification. FHWA shall take into account Tribal recommendations regarding treatment of the remains and proposed actions, and then direct MoDOT HP to carry-out the appropriate actions in consultation with the SHPO. MoDOT shall monitor the handling of any such human remains and associated funerary objected, sacred object or objects of cultural patrimony in accordance with the Missouri Unmarked Human Burial Sites Act, §§ 194.400 – 194.410, RSMo.

127.2.10 Historic Bridge Information

There are about 24,000 bridges in the state (state, county and city bridges). The 1996 Missouri Historic Bridge Inventory survey evaluated approximately 11,000 of them that were built before 1951. About 1,800 of these had some potential for NRHP eligibility and were researched in more detail. Of these, 399 were considered possibly eligible, eligible or listed on the NRHP. In 2003, a Programmatic Agreement between the MoDOT, FHWA, State Historic Preservation Office and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation accepted the results of Fraser’s 1996 survey and the 399 most significant bridges became the Missouri Historic Bridge List (with some modifications). That same year the Missouri Historic Bridge Management Plan outlined a strategy for dealing with historic bridges on the list.

Additional information on individual bridges can be found at BridgeHunter.com. Also, Context for Common Historic Bridge Types is available for reference.

127.2.11 Early Acquisition of Right-of-Way and Disposal of Uneconomic Remnants

In extraordinary cases or emergency situations, consideration may be given to acquisition of hardship or protective buying parcels within the limits of a proposed highway corridor prior to completion of the appropriate environmental document. The acquisition of hardship or protective buying parcels shall not be considered when:

- The Section 106 process has not advanced to where preliminary eligibility and effect determinations have been made to identify Section 4(f) historic resources.

- They are located within Section 4(f) land or contain historical properties that the required Section 4(f) evaluation has not been completed.

- It would influence the selection of a preferred alternative or alignment, or otherwise influence the decision of the Department on any approval required for the project.

- It would cause any significant adverse environmental impacts or cumulative effects if multiple parcels are acquired.

To comply with Section 4(f) for early acquisition requires that there is a reasonable level of effort to identify historic properties prior to issuing a Section 4(f) approval. A Phased Section 106 process to identify and evaluate historic properties has been negotiated with FHWA, SHPO and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to help develop the reasonableness of the level of effort, which depends upon the anticipated effects of the project and nature of likely historic resources present in the area of potential effects. Completion of the 1st Phase of the Phased Section 106 process is required to identify “above ground” historic properties (e.g., buildings bridges, etc.) and to document the level of effort and justification for the conclusion that it is unlikely that there are additional “below ground” historic properties (e.g., archaeological sites) that could be subject to Section 4(f).

Details on this Right-of-Way acquisition process can be found in EPG 236.3.4.4 Early and Advance Acquisition.

MoDOT considers impacts to cultural resources on uneconomic remnant and excess right of way parcels previously purchased by MoDOT for prior to their sale or disposal. If these parcels are identified early in the project, that information should be provided to the Historic Preservation Section in order that those areas are included in the initial survey of the project area. Consideration of the entire parcel to be acquired during the project development process may avoid additional trips to the project area and ensures that late discovery of significant cultural resources will not endanger any agreements between the MoDOT, SHPO, FHWA, other state or federal agencies, and the landowner.